Can screenshots be used in court?

Are they even legally admissible?

From the January 6th riots and insurance fraud, to horrific war crimes, a surprising number of people are posting incriminating evidence on social media.

But if you're trying to capture this evidence before the poster realizes the potential consequences and takes it down, or the social media platform removes the content for violating their policies, you have to act quickly.

What would you do?

Taking a screenshot online of the content seems like the easiest, most obvious choice.

Many plaintiffs, investigators, regulators, and even legal professionals resort to this method simply because there aren’t that many ways to preserve a digital copy of a social media post that exists exclusively within an online platform.

But are these screenshots legally admissible? It's a bit more complicated than you may think.

Here's what you'll find in this post:

- Are Screenshots Admissible in Court?

- What Is Metadata?

- Why Do Screenshots Need Metadata to Be Used In Court?

- Is Taking Screenshots of Messages Illegal?

- Can Screenshots of Text Messages Be Used in Court?

- Real-world Cases Where Screenshots Were Inadmissible In Court

- The Risks and Limitations of Using Screenshots in Court

- Online Evidence and Screenshot Best Practice

- How Can I Screenshot Media from YouTube, TikTok, Instagram Reels or Facebook Stories?

- The Automated & Defensible Alternative to Screenshots

- How To Screenshot Online Evidence with WebPreserver

Are Screenshots Admissible in Court?

All evidence, including screenshots, is admissible in court as long as it is relevant and does not meet any exclusion criteria.

However, the admissibility of screenshots becomes more complex when their authenticity is questioned.

To ensure that a screenshot is accepted as evidence, it must be proven that it has not been manipulated and is relevant to the case. Even if admitted, the court may not fully trust the evidence if it lacks proper authentication and context.

Screenshots, especially those from social media, present unique challenges when it comes to ensuring authenticity.

For one, manually taking screenshots and attempting to document and verify them can be a highly time-consuming and tedious process. This is because it often involves carefully capturing each relevant screen; documenting when, how, by whom, and on what type of device and operating system it was captured; organizing them in a coherent manner; and ensuring that every piece of information is accurately represented. And because social media content can be edited or deleted in real-time, it can be difficult to capture and document the entire process before the original evidence is taken down or modified.

There is also the technical challenge of making sure screenshots maintain their integrity and that images are stored in a tamper-proof format, so you can prove it has not been altered.

And if you're just taking a screenshot online, the copy that is produced will be a simple JPEG file that does not capture important metadata needed to ensure the authenticity of the evidence.

All this is to say, screenshots have significant limitations when used as evidence in legal contexts because they can be easily manipulated and, especially when not well documented, may lack the necessary metadata to prove authenticity.

What Is Metadata?

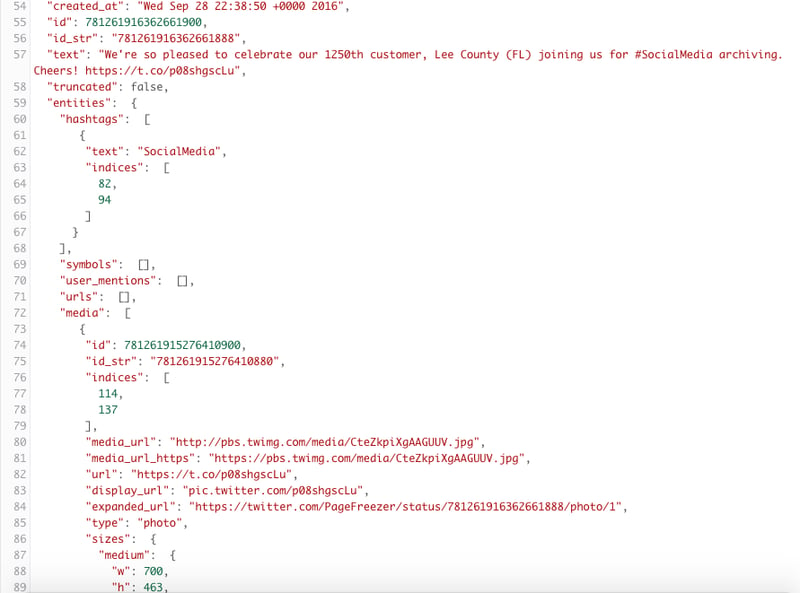

Metadata is essentially data about data—it provides details about a piece of content, such as its origin, context, and other attributes. For social media posts, metadata includes information like the author of the post, the type of message, the date and time it was published, any versions or edits, the original URLs (even if shortened), location data, and the interactions it has received, such as likes and comments.

(For a deeper dive, check out our blog post 👉 What Is Metadata? And Why Is it Important?)

Why Do Screenshots Need Metadata to Be Used In Court?

While metadata is embedded within digital content, screenshots do not capture it. This vital information is crucial for verifying the authenticity and context of a post, so you can start to see how screenshotting evidence online may not stand up in court.

Without capturing the metadata, there is no way to prove that your JPEG copy accurately represents what was originally posted on the social media platform. All you have is an image that could have been Photoshopped or manipulated in some other way—and a court, not to mention your opposing counsel, won’t be satisfied with that.

An example of a Twitter post's metadata.

Is Taking Screenshots of Messages Illegal?

But is screenshotting social media or text messages illegal?

Generally, capturing screenshots of publicly available information or content you have legitimate access to is legal. However, if the screenshots were obtained by tricking a user into accepting a friend request from counsel or a fake profile, the ethics of the evidence could be called into question.

The situation becomes more complex in cases involving privacy violations, harassment, revenge porn, or breaches of confidentiality, where unauthorized screenshotting can infringe on someone’s privacy rights. Courts have consistently ruled against those who misuse screenshots in this manner.

And although not inherently illegal, the absence of metadata and context can make screenshots unreliable as evidence. Ethical and legal concerns will arise when screenshots are altered or manipulated to distort the truth. If it is discovered that a screenshot has been edited or changed in any way or there is no clear documentation or metadata to prove its authenticity, it could mean the evidence is thrown out, which will likely damage your reputation with the court, and could have immensely negative repercussions for your case.

Can Screenshots of Text Messages Be Used in Court?

But what about digital content like texts or instant messages? Just like social media posts, screenshots of text messages can be used in court, but face similar challenges regarding authentication. Without the original metadata and context, proving that a screenshot is an accurate and unaltered representation of the original message can be difficult.

Can Screenshots Be Used In Court? In These Cases, The Answer Was No.

Courts have increasingly scrutinized the validity of screenshots, leading to several cases where such evidence was deemed inadmissible. Below are several examples that highlight the pitfalls of relying solely on screenshots in court and illustrate the critical importance of proper evidence collection methods that can withstand legal scrutiny.

1. Moroccanoil v. Marc Anthony Cosmetics

In Moroccanoil v. Marc Anthony Cosmetics, the case centered on trademark infringement and unfair competition of the word “Moroccanoil.”

Moroccanoil (the company) had registered the word with the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO). Marc Anthony Cosmetics argued that the words “Moroccanoil” and “Moroccan oil” were used interchangeably by consumers as general terms, and Moroccanoil therefore couldn’t trademark it.

To support this argument, Marc Anthony submitted screenshots of a Facebook page that illustrated how customers used these words. Unfortunately, the court ruled that the Facebook content could not be entered into evidence, since there was no way to prove that the screenshots were an exact copy of what existed on the live Facebook site. In other words, there was no way to authenticate the screenshots.

2. United States v. Vayner

During the trial of United States v. Vayner, a printout of a page on VK.com (a Russian site similar to Facebook) was entered into evidence. The defendant's legal team objected, claiming that the page had not been properly authenticated, and that there was consequently no proof that this was in fact his page.

The court agreed and the evidence was deemed inadmissible, but this decision was later overruled by a district court who argued that it was reasonable to assume that the page belonged to the defendant.

But the story didn’t end there. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit again overturned the ruling, arguing that there was no way to prove the authenticity of evidence. The court said that “the mere fact that a page with [the defendant’s] name and photograph happened to exist on the Internet at the time of [the investigator’s] testimony does not permit a reasonable conclusion that this page was created by the defendant or on his behalf.”

3. Edwards v. Junior State of America Foundation

In Edwards v. Junior State of America Foundation, a civil litigation matter involving the intentional destruction (spoliation) of social media evidence, the plaintiff had deleted his Facebook account resulting in lost evidence critical to the case.

The court cited an affidavit submitted by an eDiscovery expert witness who noted that when Social Discovery was used to collect from the Plaintiff’s Facebook account, key evidence that existed was missing because it had been deleted by the Plaintiff prior to the collection.

As a result of the spoliation established in large part by the Social Discovery examination, the Court imposed severe evidentiary sanctions on the plaintiff, including the exclusion of evidence and claims related to the destroyed Facebook data, and adverse jury instructions.

The plaintiffs’ had sought to offer screenshots as evidence of the Facebook communications instead of the deleted native files. The court ruled that the metadata and full context of the native files were essential to satisfy the Best Evidence Rule.

The court held that screenshots were not an output that accurately reflected the substance and context of the native file, since they could not show that the messages were authentic, nor could they “be used to prove that Harper sent the Facebook Messages contained in the screenshots.” Failure to produce the native files prejudiced JSA, in part, because it deprived Defendants “of the ability to substantiate or refute the authenticity of the alleged Messages.”

In a key passage, the court states:

Here, the screenshots will not suffice as an “original” because the screenshots are not an “output” that “accurately” reflect the information. Only native files can ensure authenticity. Additionally, although the Best Evidence Rule allows for an original “photograph” to prove the contents of the photograph, this does not mean that the screenshot here can be used to prove that Harper sent the Facebook Messages contained in the screenshots.

Cases like Moroccanoil v. Marc Anthony Cosmetics and United States v. Vayner underscores the importance of proper collection and authentication methods. Simple printouts and screenshots are simply not good enough.

(To see more case examples, check out these articles: 5 Times Digital Evidence Was Denied in Court and More Legal Lessons Learned: 7 Times Social Media Evidence Was Denied in Court.)

The Risks and Limitations of Using Screenshots in Court

As we’ve discussed in the previous sections and have been illustrated in the real-world court cases above, there are real risks and limitations of using screenshots in court. In summary, the risks and limitations of using screenshots in court are:

- Manipulation and tampering: Screenshots can be easily manipulated or tampered with, compromising their integrity as evidence.

- Lack of metadata: Usually screenshots lack critical technical information essential for verifying the content and authenticity.

- Lack of context and completeness: Screenshots fail to capture the full context and dynamic nature of social media posts, including comments, likes, and other interactive elements, which is essential for proving the evidence’s value in court.

- Authenticity and admissibility: Without proper documentation, context, and metadata, there will likely be strong legal challenges to the admissibility of your screenshot evidence.

- Verification and documentation: Unless you are a technical wiz and a legal expert, verifying and documenting all of your screenshots in a coherent and admissible manner will be incredibly difficult. If you miss any important technical information or miss any steps in verification, your evidence could easily be called into question.

- Timing and effort: Manually taking screenshots and documenting them is time-consuming and inefficient. Evidence could be deleted before you even have a chance to capture it.

- Technical challenges: Capturing dynamic web content accurately with screenshots is not usually possible. Only advanced, purpose-built tools can handle dynamic content and provide reliable evidence collection.

Online Evidence and Screenshot Best Practices

The prevalence of social media and online evidence is growing, but if printouts and screenshots could put your case at risk, you need to understand best practices for capturing legally admissible online evidence.

One respected authority that has been advocating for a more sophisticated approach to capturing social media evidence beyond simple screenshots is the Sedona Conference.

The Sedona Conference is a research and educational institute dedicated to the advanced study of law and policy. It focuses on the areas of antitrust law, complex litigation, intellectual property rights, and data security and privacy law.

One of its seminal publications is The Sedona Conference Primer on Social Media, which received a second edition in 2019. The preface of the latest version explains the reason for its creation:

“The need for an updated Primer was essential given significant advances in social media technology since we published the first edition of The Sedona Conference Primer on Social Media in December 2012. The proliferation of messaging technology and its usage—on traditional social media platforms and in mobile messaging applications—have created preservation, production, and evidentiary challenges that counsel should learn to recognize and address.”

Predictably, The Sedona Conference specifically addresses the use of screenshots and other static images in its social media primer. The document states that:

“Some practitioners resort to capturing static images of social media data (i.e., screen shots and PDF images) as a means of preservation, with courts often permitting the use of such evidence at trial. Printing out social media data has its evidentiary limitations, as a static image does not capture the metadata of the image, other than whatever information may be viewable as part of the screen shot. As a result, static images may result in an incomplete and inaccurate data capture that is hard to authenticate, except on the basis of the personal knowledge of a witness. Social media may also contain data and content, such as video, that cannot be properly collected in the form of static images. In addition, social media outlets use different interfaces to display content, further complicating efforts to create standardized snapshots. Any such collection will most likely be a visual representation that does not include metadata, logging data, or other information that would allow the content to be easily navigated and used.”

In short, a screenshot has three problems:

- First (and most crucially), it lacks the hash values and metadata needed to prove authenticity.

- Second, it lacks context and gives you no real understanding of how the social media content is presented.

- Finally, it cannot capture related media (like videos or GIFs) that are likely needed to understand the purpose and context of a post. With video becoming the new norm on nearly every social platform, this raises major challenges.

How Can I Screenshot Media from YouTube, TikTok, Instagram Reels or Facebook Stories?

Capturing media from platforms like YouTube, TikTok, X (formerly Twitter), Instagram Reels, or Facebook Stories presents unique challenges. These platforms are filled with short-form videos, including quite a bit of controversial or criminal content that is often quickly deleted.

While taking static screenshots is possible, they lack essential metadata and context, making them insufficient for thorough documentation. To effectively capture content from these platforms, a web evidence capture tool is necessary, allowing you to download the full video along with all associated metadata and related content.

The Automated & Defensible Alternative to Screenshots

So, if screenshots aren’t the answer to social media evidence collection, what is?

The Sedona Conference highlights the value of turning to specialized vendors that can provide dynamic capture with metadata. These vendors have developed technology that allows certain content to be collected in a way that preserves it while capturing various metadata fields associated with social media data. Properly captured, these metadata fields assist with establishing the chain of custody and authentication and facilitate more accurate and efficient data processing and review.

That is precisely what Pagefreezer’s WebPreserver forensic preservation tool is designed to do. WebPreserver simplifies online evidence capture by automating collections and providing defensible exports that can be used in court.

WebPreserver capturing an entire Facebook timeline in seconds.

With WebPreserver, you can:

-

Collect website and social media evidence with two simple clicks

- Use bulk-capture features to collect entire websites and social media accounts

- Provide OCR PDF output for eDiscovery systems

- Quickly collect and authenticate videos from websites, YouTube, Facebook, X, TikTok, Instagram, and other websites

- Generate MHTML and WARC files for forensic-ready evidence

- Maintain complete control over the chain of custody

- Automatically scroll through timelines and expand comments

How To Screenshot Online Evidence with WebPreserver

The best way to collect online evidence is to use technology like WebPreserver to capture metadata and context so the evidence can stand up in court.

How to use WebPreserver to capture legally-admissible online evidence.

For legal and investigative teams looking to collect social media or web content, WebPreserver significantly reduces the time and effort needed to gather this evidence. Instead of spending weeks or months taking screenshots, WebPreserver automates the collection process and captures entire social media accounts with minimal effort. And unlike screenshots, you’ll have access to authenticated records that can stand up in court.

WebPreserver also automatically preserves embedded video content as forensic evidence. WebPreserver will collect all videos within your specified preservation scope, and make them available for immediate download, along with all other associated content.

How to use WebPreserver to capture videos and all associated comments.

Instead of simple file exports that can be doctored, or risk accusations by opposing counsel that the videos you collected might be AI generated or deep fakes, you’ll have the original, authenticated video to submit as evidence.

Watch the video to see WebPreserver in action

Ready to learn more about WebPreserver?